In this post, I’ll share what surprised me most about building an LLM from scratch—where structure finally became visible.

I wanted to write an autoregressive, transformer-based, decoder-only Large Language Model—like GPT, LLaMA, etc.—without too many abstractions and hand-holding.

Andrej Karpathy, ARENA, Sebastian Raschka, Stanford's various courses, Neel Nanda, and many others, are all wonderful resources.

But, ultimately, nothing beats the learning that comes from getting your own hands dirty.

In writing the architecture from scratch, I finally internalized things I’d previously treated as architecture "trivia": LayerNorm vs. RMSNorm, learned positional encodings vs. RoPE, GELU vs. SwiGLU. More importantly, I realized that there was no interface that matched how these systems now existed in my head—as interacting design choices rather than static diagrams.

So, initially with Streamlit and then evolving to FastAPI and NextJS, I built an interface—with the help of various AI coding tools including Claude Code, OpenAI's Codex, and Google Antigravity.

I deployed a limited functionality version to buildanllm.com; you'll have to clone the repo and pay for your own compute!

This project is not optimized for speed, cost, or even output quality. It is optimized for learning. The code is clean, modular, and heavily commented. The interface surfaces diagrams, equations, and code specific to the configuration you’ve chosen, rather than presenting a single frozen architecture.

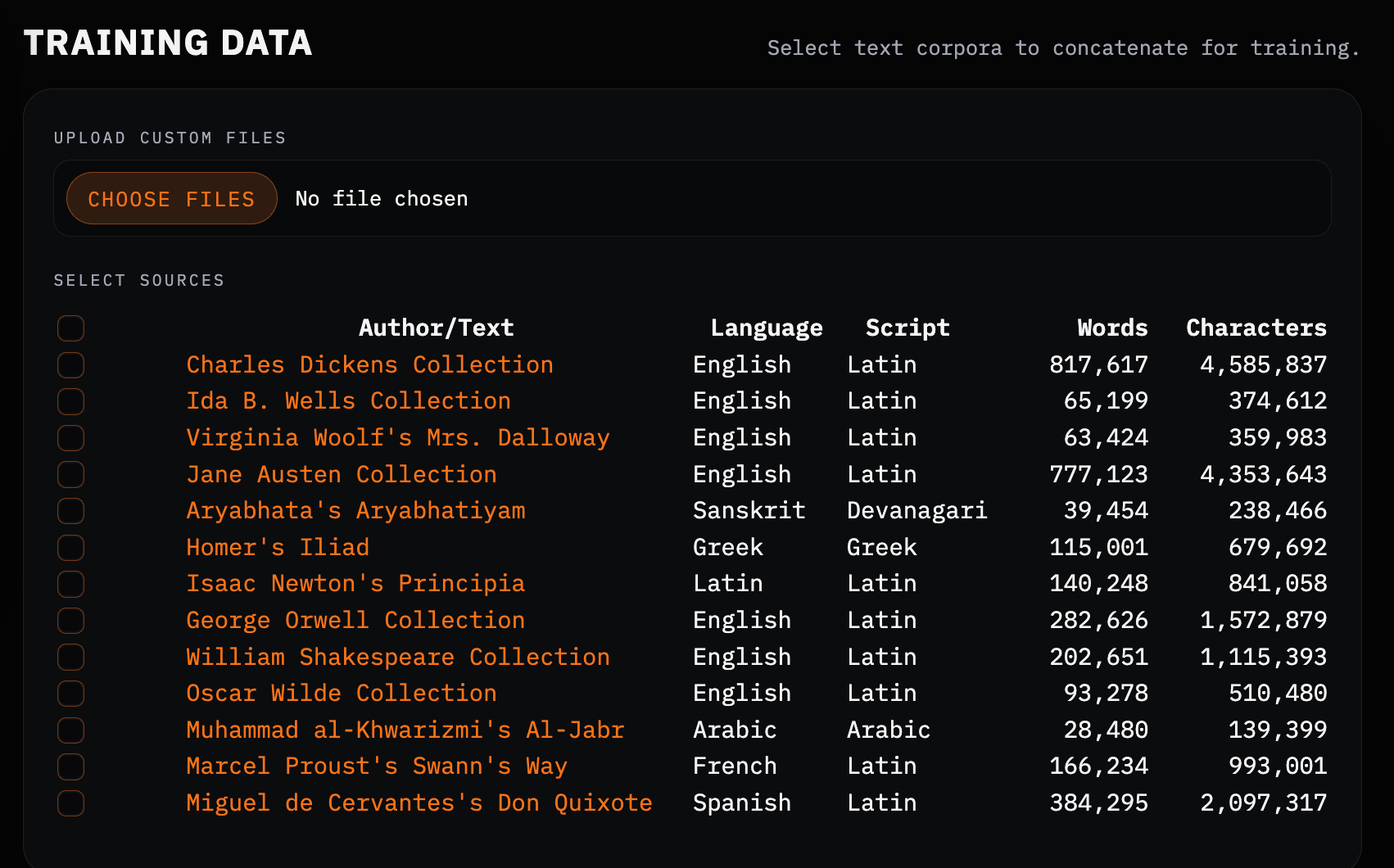

Training Data

First up is the training data. You can upload your own file(s), or select from a small but intentionally diverse set of defaults—spanning languages, scripts, and history. This choice matters far more than I initially expected, and has an impact in architectural decisions to come.

Architecture

Next comes the fun part: choosing the architecture.

I included presets that roughly match canonical designs. GPT-2, as those who’ve watched Karpathy’s walkthroughs will know, uses learned positional encodings rather than RoPE, LayerNorm rather than RMSNorm, and GELU instead of SwiGLU. LLaMA makes different—and in many cases more elegant—choices. Its attention mechanism is also more efficient (Multi-Query Attention), and modern variants introduce Mixture-of-Experts layers in the MLP blocks.

Seeing these choices side-by-side, rather than buried in code or papers, made clear that there is no single "transformer architecture"—only families of trade-offs.

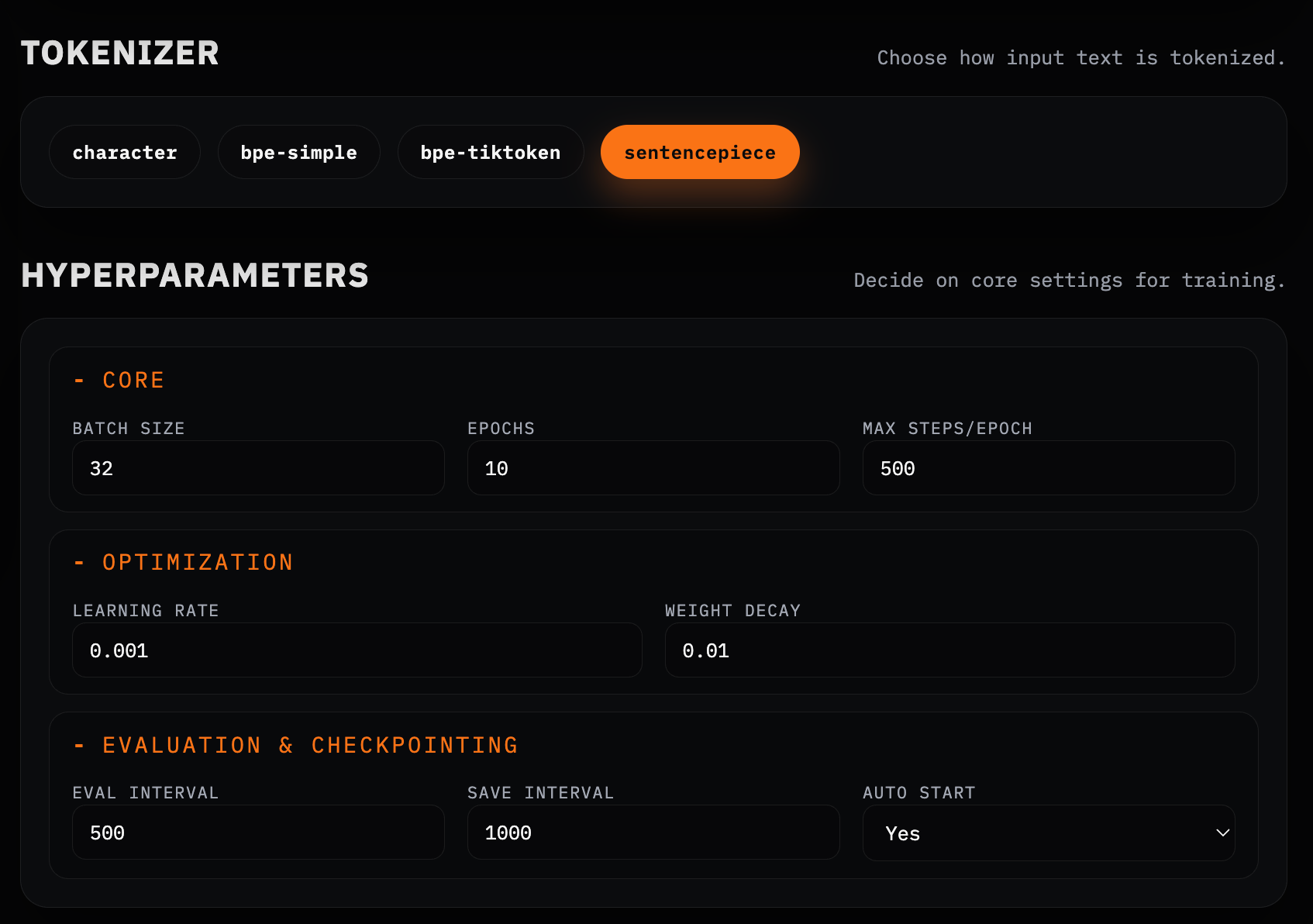

Tokenization and Hyperparameters

Tokenization, however, was where my intuitions failed most dramatically.

Karpathy’s GPT-2 demo uses simple character-level encoding, where every character is its own token. GPT-2 itself used byte-pair encoding (BPE). More modern models often use SentencePiece.

What surprised me was not that these differ—but how they differ across languages and scripts. BPE, trained largely on Latin-script corpora, can be structurally blind to languages like Arabic. SentencePiece, operating directly over Unicode without hard whitespace assumptions, preserves meaningful subword structure far more effectively.

Tokenization is not a neutral preprocessing step. It is, like so much else here, an inductive bias—one that silently determines what kinds of structure a model can even hope to learn.

A stark demonstration of this would come further on when I trained on non-Latin texts.

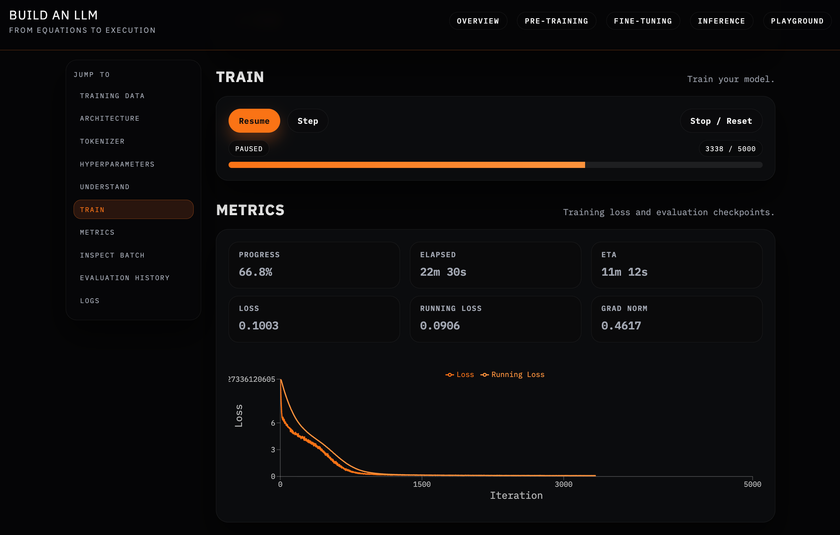

Training

Then comes the obvious milestone: watching the training loss fall as the model improves at next-token prediction.

But that view is still abstract.

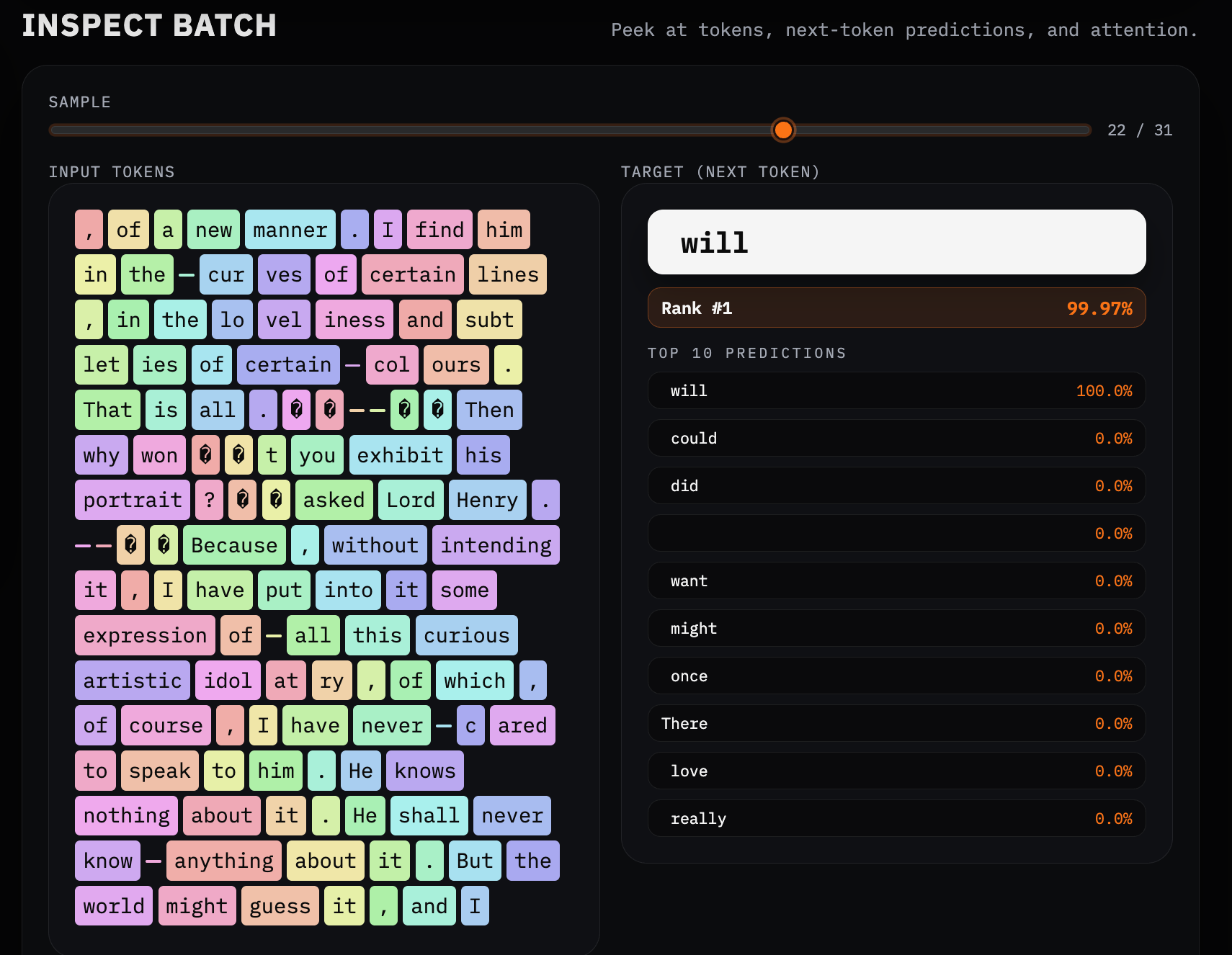

The real moment of clarity came from inspecting a single element of a single batch. Here, for example, the model assigns a 99.97% probability to the word "will" as the next token. (That's because we're two-thirds of the way through training.)

This is no longer a curve or a scalar. You can see the alternatives the model considered, how sharply it prefers one continuation over others, and—crucially—which tokens it was reasoning over in the first place.

Notice the difference between BPE and SentencePiece on Arabic script (from Muhammed al-Khwarizmi's Al-Jabr, from where we get the words algebra and algorithm, both underlying this work).

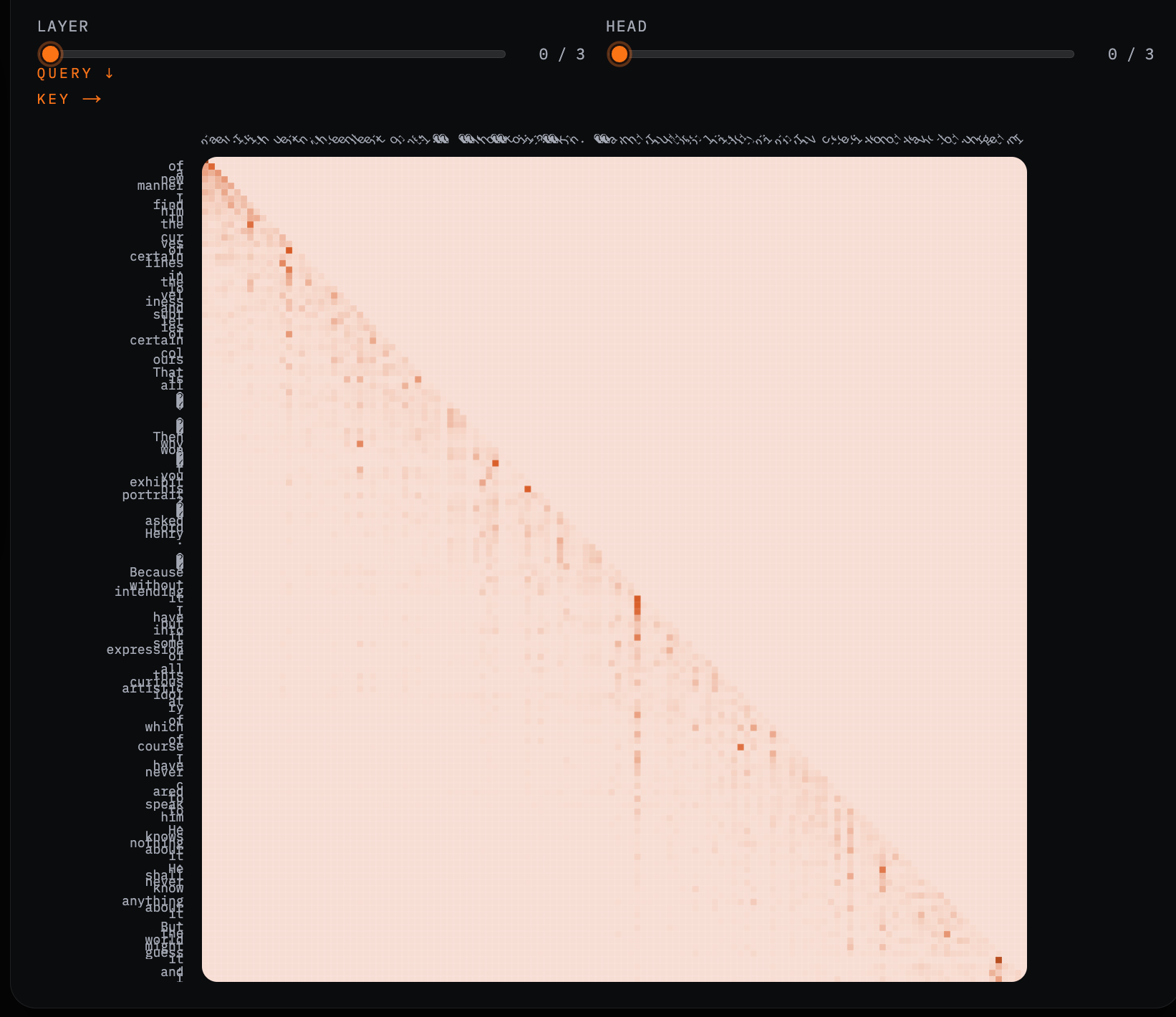

I also surface the heart of the transformer: attention itself.

For any given sample, you can inspect an attention heatmap showing which tokens attend to which others—layer by layer, head by head. This is the first place where the model stops feeling like a loss-minimizing machine and starts to feel like a system with internal structure.

The diagonal band of causal attention is expected. What’s more interesting are the deviations: long-range dependencies lighting up, punctuation acting as anchors, and certain tokens consistently pulling attention across heads. These patterns aren’t obvious from equations alone—and they’re completely invisible from loss curves.

Seeing attention in context makes it clear that what the model can attend to is downstream of earlier choices: tokenization, context length, positional encoding. If those are broken, attention faithfully amplifies the wrong structure.

Inference

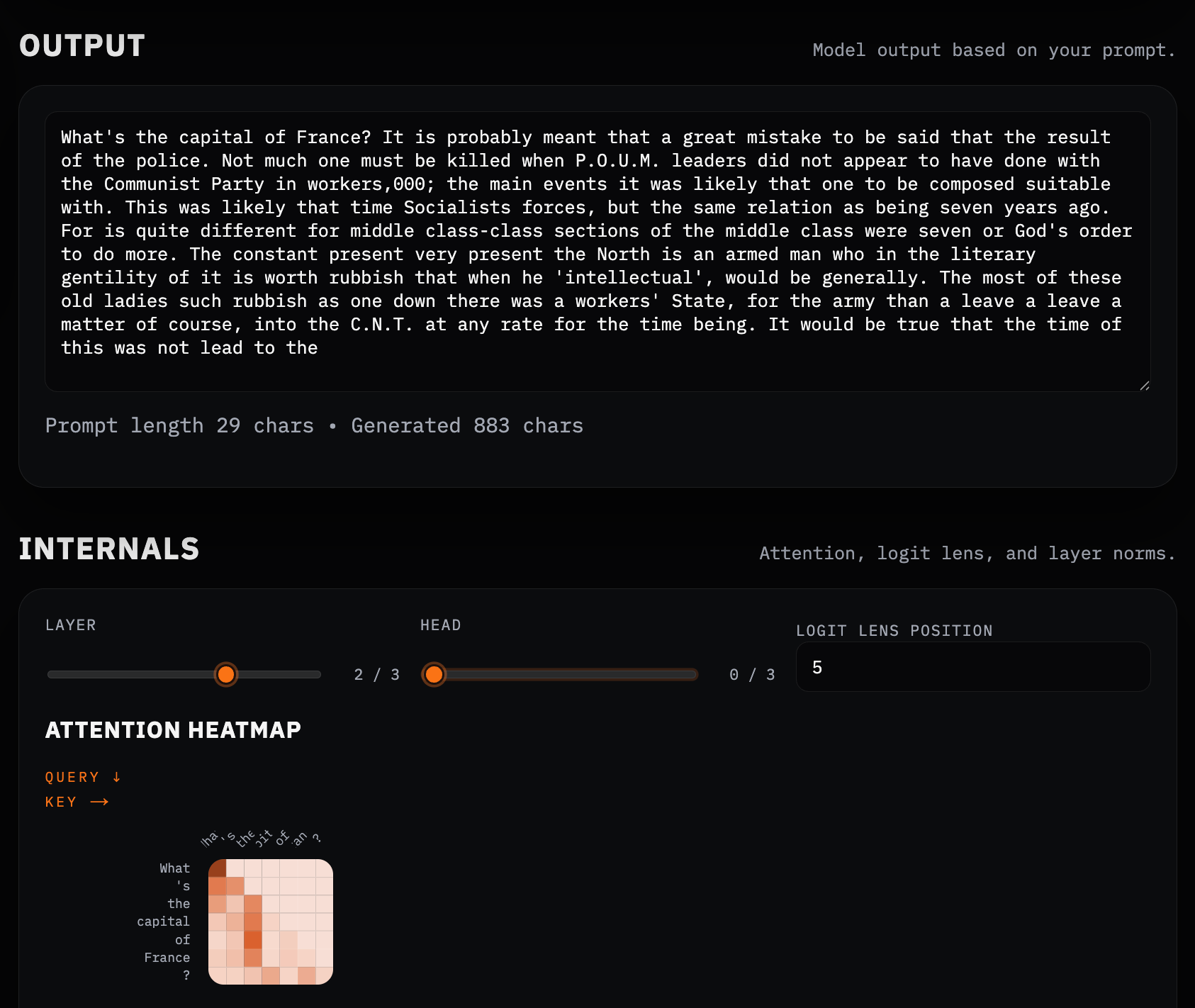

Now, we have our fully pre-trained model! It's not finetuned, so won't answer questions, but let's try anyway!

What's the capital of France?

It doesn’t quite get there. But that’s not the interesting part.

What is interesting is that, after roughly half an hour of training on a consumer laptop (a MacBook Pro M3 Max with 64 GB of RAM), and using just ~280,000 words of George Orwell, the model already produces coherent English and locally sensible continuations—even if global structure hasn’t yet emerged.

This is where inspecting internals matters more than judging outputs. You can see why the model fails: what it attends to, which continuations it considers plausible, and how earlier design choices constrain everything downstream.

Next Steps

Fine-tuning is the obvious next step, and I’ve written code and functionality for that as well—both full-parameter fine-tuning and LoRA. That’s the path any real-world LLM lab would follow.

But the value here isn't in rushing forward. It's in solidifying what we've already built: how data becomes tokens, how tokens become attention patterns, how architectural choices constrain everything downstream. The goal is to reach the point where the equations, the implementation, and the behavior all feel like the same object viewed from different angles.

If that sounds useful to you: clone the repo, pick (or create) a dataset, choose an architecture and configure it, and watch attention and tokens emerge.